American Premiere of Ravel's Bolero in 1929

HISSES HAVE FOLLOWED THE RENDITION of much modern music, but joy would have warmed the heart of the Frenchman, Ravel, to hear the shouts and plaudits following Toscanini's conducting of his "Bolero." The composition is a year old, and was presented, two weeks ago, for the first time in New York. Carnegie Hall rocked; and music critics were rapt out of their megrims in describing the effect of this electric composition. The music depicts a Spanish dance, and in the analysis by Olin Downs of the New York Times, shows that "this master of modern musical speech builds his tonal structure over the simplest possible harmonic bass, and makes exactly one modulation from key, at the final climax." Further:

The piece is in itself a school of orchestration. It is not great music, but the craft, the virtuosity, the racial understanding in it—Ravel was born, remember, in Ciboure—are really thrilling. It is no more nor less than a 'jeu d'esprit' by two masters— the one of the means of composition, the other of the interpreting orchestra. They held carnival together, and it was not astonishing that the audience shouted."

The critic of The Morning Telegraph purges himself by translating his emotion into words:

"For twenty minutes or more 'Bolero,' the new work of

the Frenchman, Ravel, was unwound for the first time in

America, by Arturo Toscanini, yesterday and Thursday, at Carnegie Hall.

"When 'Bolero' had completed perhaps ten minutes of

sinuous way, I gasped and prest my heart, which pounded.

When another five minutes had passed, one thought possest me:

'Marvelous, miraculous music; fundamental, simple, primitive,

low-down, earthy, but the essence, the pure residue, the actual

metal.'

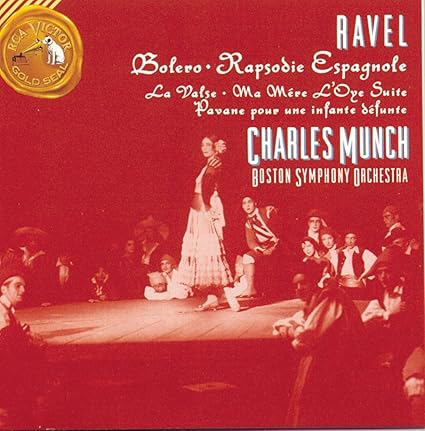

"When 'Bolero' had its premiere in Paris a year ago, Ida

Rubenstein, to whom the score is dedicated, danced to its

measures, depicting a scene in an inn in Spain. 'A woman

dances on a trestle table; the men who surround her, calm at

first, work to a frenzy, knives are drawn, the woman is tossed

from arm to arm, her partner intervenes, and they dance until

dawn.' So the program note read. I could see that woman,

behold the mob, fiery-nostriled, blood-boiling.

"When, after the theme had been tasted, chewed, digested,

thrown about, tossed, kneaded, jumped upon, and finally the

whole orchestra in one ferocious, savage ensemble fought for it,

piling one upon another, I knew another moment and I should

go mad.

"Suddenly: disintegration, the fiendish phrase breaks to

pieces, a crash—and silence.

"So was played the foremost new work for orchestra, of at

least a decade. Personally, I do not recall any premiere to

have been received vith such a reception as was given it by the

emotion-loosed audience. The yells and hand-clapping came

down like an earthquake. It did not subside. And even after

Toscanini had tapped for the next opening, the applause broke

out afresh.

Source: The Literary Digest for December 7, 1929